Roman Dodecahedron Solved by the Ezekiel Project

The Roman dodecahedron is one of the most enigmatic artifacts from antiquity. These small, hollow objects, typically made of bronze or sometimes stone, are characterized by their geometric shape: a twelve-faced polyhedron, with each face a regular pentagon. Each pentagonal face has a circular hole of varying diameter in its center, and small knobs are often positioned at the vertices where the faces meet. Despite the many examples of dodecahedra unearthed across the territories once held by the Roman Empire, especially in regions corresponding to modern-day France, Germany, and Great Britain, their exact purpose remains unknown, sparking a wide range of theories and continued fascination among historians, archaeologists, and enthusiasts alike.

Roman dodecahedra date broadly from the 2nd to the 4th centuries CE. They have been found primarily in the northern provinces of the Roman Empire, territories that were often considered frontier lands rather than the empire’s urban, Mediterranean core. Interestingly, they are absent from the heartlands of Rome itself, a detail which has led some scholars to suggest that they might have had a specific purpose unique to the regions where they were discovered. Despite being found in a wide range of sites—graves, military camps, and even civilian settlements—there is no ancient written record, inscription, or depiction that clearly explains their use. The Roman authors who have bequeathed to us volumes on architecture, warfare, religion, and daily life seem never to have mentioned them.

Over time, a multitude of theories have been proposed regarding their function. One popular suggestion is that they were used as measuring instruments. Given the different sizes of the holes on each face, some believe they could have been used to calculate distances or measure standard sizes of objects like pipes or poles. Another interpretation posits that they served as survey tools, perhaps in agriculture or construction. The irregularity of the hole sizes might have allowed a user to sight an object at a known distance through differently sized apertures, allowing for rough distance estimation.

Others have proposed that the dodecahedra had a ritualistic or religious function. Some were found in graves alongside other personal objects, hinting that they might have served as talismans or ritual objects. Their complex geometry and symmetrical beauty could have imbued them with symbolic significance. The fact that the dodecahedron has twelve faces might also suggest a calendar-related function, tying into the twelve months of the Roman calendar or perhaps astrological or cosmological systems. Some speculative theories even imagine the dodecahedra being used in fortune-telling practices, somewhat akin to later medieval geomancy.

Another idea is that they could have been used in a more domestic context. Some suggest they were tools for knitting or weaving, specifically for creating gloves. The varying hole sizes could theoretically help size the fingers of gloves accurately. However, there is little concrete archaeological evidence to back this up, and no examples of corresponding knitting needles or instructions have been found alongside dodecahedra. Nonetheless, the glove theory persists among certain hobbyists who have successfully replicated knitting patterns using models of these objects.

Military theories have also been proposed. Since some dodecahedra have been found at Roman military sites, it has been suggested they were related to artillery or surveying in a military context, possibly functioning as part of a sighting mechanism or a compact tool for range finding. However, the lack of standardization between different dodecahedra—each seems unique in size, shape, and hole diameter—makes their use as standardized military tools less likely.

The craftsmanship of Roman dodecahedra is another point of intrigue. They are often cast in bronze and show a high level of technical skill, but they do not appear to have been mass-produced in a way that suggests a ubiquitous, everyday tool. Rather, each seems to have been individually crafted, with slight variations that argue against a standardized functional use. This uniqueness could support the theory that they were prestigious items, perhaps symbols of status or local identity in the Roman frontier regions.

The Report from Ezekiel (Pseudonym):

Now I will tell you in my own words what I encountered during the remote viewing session. As a starting point for the remote viewing, I used a photograph of an original artifact.

We have set up a special room for remote viewing, free from light emissions, and environmental sounds are prevented from reaching the remote viewer through insulation. In order to carry out a remote viewing session, I need a few minutes of deep concentration. At some point, without being able to control it myself, I break through a barrier that can be compared to the acceleration one feels on a roller coaster. Moments later, I find myself in a scene that the photo or artifact has triggered. From this point on, I have no control over time or place. I am present, but I cannot intervene nor am I perceived by others.

This time, I find myself in a temperate climate zone, the temperature is pleasant, and I am standing in front of a building, entering through an unlocked entrance. It smells of horse. As I proceed further, the air smells of human sweat. Several men are in the process of undressing. They are smaller than I am, about 160 to 170 cm tall, with dark hair. They are conversing in Latin. I do not understand the words, but I can perceive their thoughts.

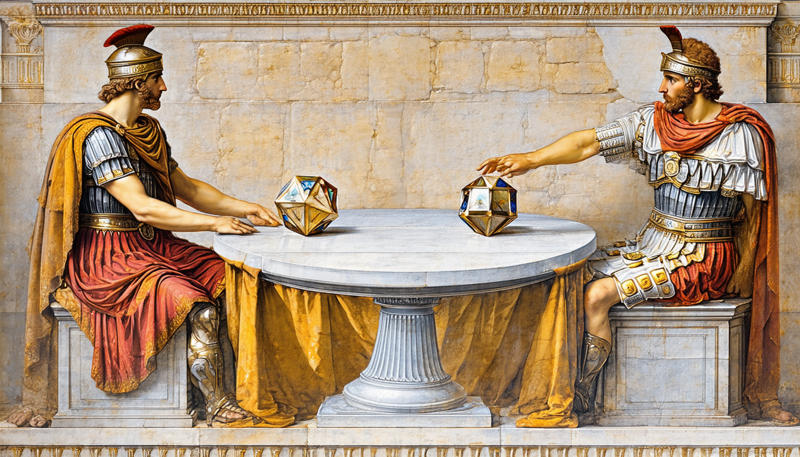

I move further into the building. Two men are sitting at a round table. I see two of the artifacts on the table, next to six-sided dice with dots ranging from one to six. One die is light-colored, the other three are black. Wooden round symbols, roughly the size of a large coin, are inserted into the openings of the dodecahedra. I see a horse’s head on one, and a shield on another.

The two men are soldiers, and they are playing with the light-colored die. Each dodecahedron belongs to one player. Other men stand around the table, watching. One man rolls the die and then tips the artifact over an edge corresponding to the number rolled. The artifact must always be tipped over two knobs into the next adjacent field. The men take turns. The round table is about 45 to 50 centimeters in diameter and simultaneously serves as the boundary of the playing field. The artifacts must not touch each other. Therefore, one can block the opponent’s path with one’s own artifact. The game is played over seven rounds, each man rolling alternately. Toward the end of the seventh round, the players attempt to bring their desired symbol into the uppermost position.

Afterwards, the men roll the three black dice, and according to a point system, the symbol with the most points wins. It is a game of great significance. According to their belief, the gods guide the dodecahedron. Thus, the outcome of a game could be seen as a fateful decision, used to determine a battle strategy. If the cavalry succeeded significantly in the game, a commander might interpret it as a sign and employ them in the next battle to fight the enemy. If a player had a preference, he could insert his preferred symbol into a designated spot within the dodecahedron. It was not merely a game to entertain the men, but in exceptional cases, it could also determine the strategy of a battle.

The wooden symbols were inserted into the openings like corks.

The session ended abruptly at this point. I couldn’t gain any further insight. It felt like I had watched the game for about an hour, but according to the running clock, I was in the remote viewing state for just over four minutes.

Remote viewing sessions of this kind are very exhausting. You have no control over your body for the duration of the session, and sometimes you even think you’re having a stroke because parts of your head develop a gentle pressure.

The purpose of the Ezekiel Project is to stimulate discussion with insights. If mainstream archaeology is unwilling to take certain paths, we must take those paths.

With that in mind, I look forward to the next time, yours, Ezekiel!

Rules of the game:

Each player takes turns rolling a die a total of 7 times. On each turn, the player may tilt the dodecahedron over an edge equal to the number shown on the dice.

The dodecaedra may not touch each other, and the dodecahedron may not leave the square. Then, a duel begins with three dice, each rolling one roll. The respective top symbol counts. For example, infantry fights against cavalry. A point system (unclear) determines the winner.

The loser removes the wooden symbol from their dodecahedron. The game continues until one player resigns or has no more symbols/units.